Back in 2007, Arc Financials’ Peter Tertzakian was a guest lecturer for my University of Calgary energy management course and spoke about the global and Canadian oil and gas sector while also highlighting topics from his book 1,000 Barrels a Second. Over my twenty-year career I have never met someone that could so succinctly explain the complexities of the oil and gas sector the way Peter can. From the historical shifts in energy use to the economic, social, and technological factors driving transitions between energy sources, he was able to connect with the class through personal anecdotes, while also explaining the underlying factors driving the industry’s growth. And yes, he signed my book which I still have on my shelf to this day. Fast forward to 2016, Peter and Kara Jackeman published The Fiscal Pulse of Canada's Oil and Gas Industry, which I still view as the single best research report that I have read (link). The report took a unique approach of analyzing Canada’s upstream sector like an equity research analyst would a publicly traded Exploration & Production (E&P) company. The style and approach to market intelligence was unlike anything I had read and sparked my interest in research, modeling, and analysis of the energy sector. Since coming back from my time in Houston, and really since starting this newsletter series, I have set out to develop and refine my own modeled version of Canada’s oil and gas sector.

Specifically, I wanted to answer two questions:

What does Canada’s aggregated upstream sector look like operationally as well as financially?

Is the industry in better shape than in previous years and what are the trends that support my outlook for 2025?

While I do not believe I can hold a candle to the depth and breadth of research that Peter and the Arc Financial team have published over the last 30+ years, I will certainly attempt to replicate. So, with that preamble, here is part 1 of my national-level assessment of Canada’s upstream hydrocarbon sector.

CANADIAN UPSTREAM PRODUCTION

Canadian production has been on a steady increase over the past decade, with a 10-year CAGR of 2% and expected YoY production growth of 2%. Oil Sands development has the been the primary driver to Canada’s production growth at a 4% CAGR over the past 10 years. While Suncor Energy’s (SU) Fort Hills Oil Sands project was the most recent new mine development to be completed back in 2018, debottlenecking and in situ project expansions continue to drive Oil Sands production growth. By comparison, convention oil production has grown at a 1% CAGR since 2015, with YoY oil production growth expected to reach 3%. Canada’s conventional oil production growth has lagged our counterparts in America where Lower 48 oil production has realized a 10-year CAGR of 4%, highlighted by its two largest producing states, Texas, and New Mexico, which have 10-year CAGRs of 5% and 17%, respectively. Lagging growth can be equated to market access with takeaway capacity constraints being an ongoing bottleneck for Canadian producers. However, the recently completed TMX project effectively triples takeaway capacity from Alberta to British Columba’s coast with nameplate capacity increasing from 300,000 bpd to 890,000 bpd. While improved price differentials have been a byproduct of TMX since it came online in May 2024, the likelihood of comparable pipeline expansion projects appears unlikely. As such, Canadian oil production should be expected to grow no greater than 2-3% YoY for the remainder of the decade.

For natural gas, national-level production growth has been hampered by the reality that North America is awash in natural gas. With 10-year CAGR under <2%, natural gas production was effectively flat before post-COVID surges in demand accelerated production growth in 2021 and 2022, before flattening out in 2023 and 2024. While Alberta gas production has experienced successive years of production growth following COVID, current 2024 production results are expected to finish modestly down-to-static YoY at 13.1Bcfpd. To the West and buoyed by LNG commercial arrangements not only with LNG Canada, but also to LNG export terminals in the Gulf of Mexico, BC’s YoY gas production growth has accelerated since the start of COVID growing from 5.2Bcfpd in 2020 to ~7.2Bcfpd in 2024, a 9% 4-year CAGR. With LNG Canada anticipating a Summer 2025 operational start of its initial two trains representing 1.9Bcfpd in export capacity, expectations are for BC to enjoy YoY production growth of ~5% for 2025 and beyond.

Collectively, Canada’s oil-equivalent production is projected to finish the year at ~8.7MMboepd, with oil and NGL-related liquids accounting for 61% of total production. This oil cut has remained consistent over the past 10 years with an oil-weighted upward swing in 2019/2020 due to the combination of Oil Sands production ramp and COVID-related production declines.

OIL SANDS PRODUCTION

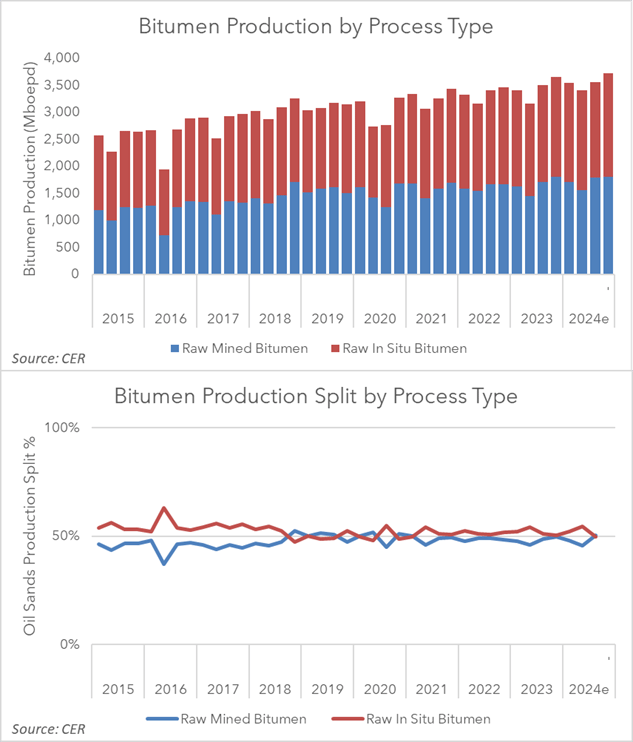

Much like the Permian basin for our American counterparts, the Oil Sands are foundational to Canada’s hydrocarbon story, accounting for 38% of national production on a BOE basis. Production is categorized by two extraction methods: mined bitumen and in situ bitumen. These two methods account for a 50/50 split in total Oil Sands production, though quarterly production variances indicate that in situ development has produced ~52% of Oil Sands production since COVID.

Utilizing a “truck and shovel” operation, bitumen mining recovers the Oil Sands deposits that are less than 75 meters below the surface and transported to an extraction facility for further processing, and either transported to one of Alberta’s eight upgraders, or pipelined to American refineries capable of refining bitumen and/or heavy crude oil blends, particularly in the US Midwest, the Rockies and to the Gulf Coast. Across the nine mining pits in northeastern Alberta, FY24 mining production is expected to average 1.7MMboepd, representing a 10-year CAGR of 4.4% and YoY growth also at 4%. While new mine development represents a step-jump in aggregated mining production due to the scale of operation, the “financial risk versus reward” reality makes it difficult to get approval for a multi-billion-dollar project approval. Having worked for Petro-Canada on the Fort Hills Oil Sands project back in 2008/09, I can attest to the risks associated with extended project horizons and cost escalation risk when compiling a construction estimate for the executive team to present to the board of directors. Factor in commodity price volatility and an ever-evolving role that Oil Sands development plays in Canada’s energy transition and you quickly realize why the most recent mine development – Fort Hills (completed in 2018 at a project cost of $17B) – may well be the last new mine constructed. As a result, mining production growth is largely defined by debottlenecking and replacement projects to improve capacity – and thereby production – across the mining process.

For in situ bitumen production, the bitumen recovery process involves extracting bitumen from deep underground deposits without mining. The most common method is Steam-Assisted Gravity Drainage (SAGD), where two parallel horizontal wells are drilled into the Oil Sands formation. Steam is injected into the upper well to heat the surrounding bitumen-rich sands, reducing its viscosity. The heated bitumen flows downward, aided by gravity, into the lower well, where it is collected and pumped to the surface. Across twenty-nine in situ projects across northeastern Alberta, FY24 in situ production is expected to average 1.8MMboepd, representing a 10-year CAGR of 3.4% and YoY growth of 4%.

Overseas talent with U.S. caliber resumes

Use Oceans to hire full-time finance talent and save over $100,000 a year.

✔ Deliver accurate forecasting and data-driven insights

✔ Build financial models to guide smarter decisions

✔ Help optimize profitability and cash flow

At Oceans, you get top-tier talent for just $36,000 a year.

COMMODITY PRICES & MARKET ACCESS

CRUDE OIL

The supply and demand relationship for Canadian crude oil pricing, and its price differential to West Texas Intermediate (WTI) spot price is shaped by market access, egress capacity constraints, and the quality of crude oil. Western Canadian Select (WCS), a heavy crude benchmark, typically trades at a discount to WTI due to its lower quality and higher cost to refine. This differential is further widened by egress constraints from Alberta, where pipeline capacity has struggled to keep pace with growing Oil Sands production. Limited takeaway capacity on major pipelines, such as Keystone and Enbridge's Mainline, has historically forced producers to rely on higher-cost rail transport, increasing the WCS-WTI spread. Recent pipeline expansions include Enbridge’s Line 3 Replacement in 2021, and the TMX pipeline project completed in 2024 have provided relief, but forecasting production out to 2028 suggests future pipeline bottlenecks occurring unless additional takeaway capacity is constructed.

For Synthetic Crude Oil (SCO), an upgraded crude product derived from Oil Sands bitumen, often trades closer to WTI due to its higher quality and ease of refinement. However, even SCO pricing has experienced pricing pressure during pipeline outages or during periods of high seasonal production. US Gulf Coast refiners, which are major buyers of Canadian heavy crude, benefit from WCS's discounted pricing but are limited by logistical hurdles in accessing Alberta's crude. Demand fluctuations, particularly during refinery maintenance or global market shocks, exacerbate price volatility. As a result, Canadian crude prices and their differentials relative to WTI are a function of infrastructure constraints, quality of product, and broader supply/demand imbalances in both regional and North American markets.

NATURAL GAS

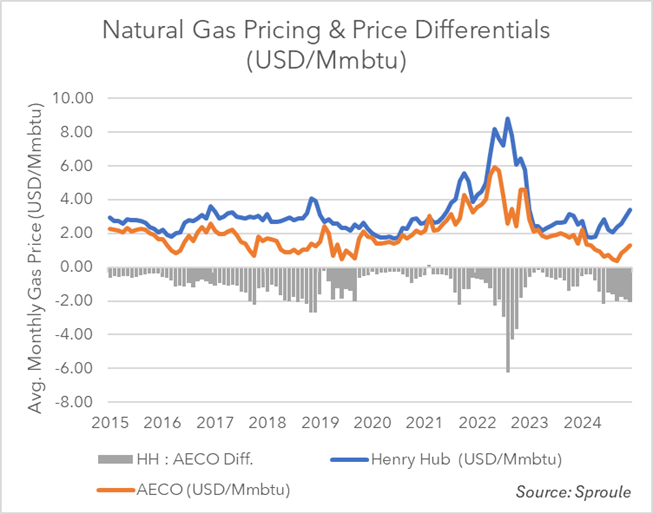

The supply and demand dynamics for Canadian natural gas, benchmarked to AECO pricing, and its differential to Henry Hub spot pricing are primarily driven by market access and egress capacity constraints. Canada’s natural gas production, predominantly from BC and Alberta, has grown substantially in recent years, particularly in the Montney and Deep Basin resource basins. However, limited pipeline capacity to transport gas to key markets has created a supply glut in Western Canada. This oversupply often suppresses AECO prices relative to Henry Hub, particularly during periods of high production or when seasonal demand in Canada is low.

Egress constraints, including pipeline bottlenecks on pipeline systems like the NOVA Gas Transmission system (NGTL) and delays in expanding infrastructure, exacerbate the situation by limiting exports to US markets and LNG terminals. While recent expansion of the NGTL system in 2021, and the pending operational start of LNG Canada have alleviated some pressures, the lack of sufficient capacity has kept differentials wide during peak production periods. Conversely, periods of reduced production during seasonally high demand periods, like a Canadian winter, can narrow the differential temporarily.

The AECO and Henry Hub price differential finished this past year averaging ~ $1.50/GJ CAD, which has widened from 2023 when the price differential averaged $0.78/GJ CAD. Expectations are for the price differential to continue widening, albeit at a slow pace, for 2025 and beyond.

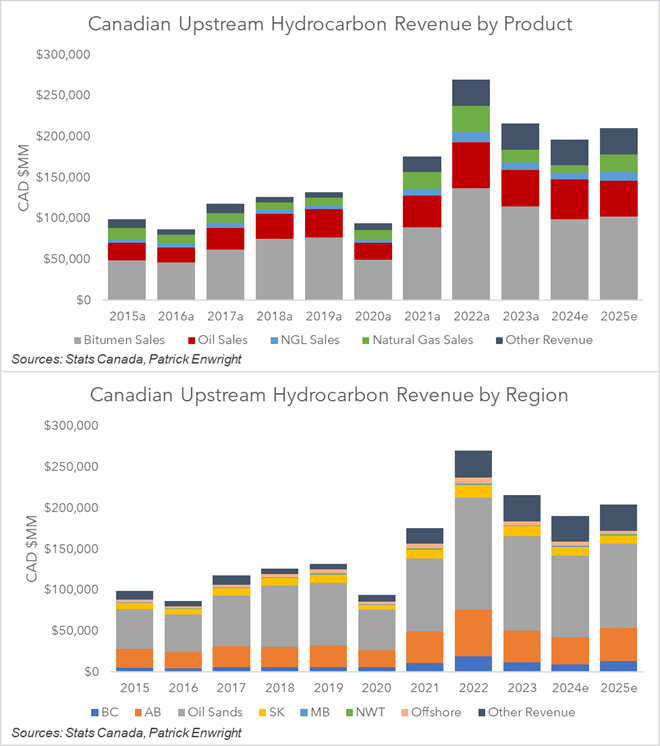

UPSTREAM REVENUE

Exploration and Production (E&P) companies produce a range of hydrocarbons that vary in type and quality. In turn, annualized revenues are calculated by the product-specific commodities pricing, and the production volumes by product type as outlined above. While Canada’s conventional oil, natural gas and NGLs collectively account for ~$66B in estimated 2024 revenue, Oil Sands revenue stands out as the pivotal economic driver to Canada’s upstream revenue, accounting for ~$100B or a little over 50% of total revenue. Drilling into the data further, bitumen mining operations effectively account for ~25% of Canada’s upstream hydrocarbon revenue. This truly illustrates the scale and significance of bitumen mining, especially when you consider that the nine operational mines are owned by only four E&Ps: Suncor Energy (SU), Canadian Natural Resources (CNQ), Imperial Oil (IMO), and Syncrude (a JV owned by SU, IMO, Sinopec & CNOOC).

For conventional oil and liquids-related revenue, the revenue trend over the past ten years has remained relatively consistent accounting for 26-29% of total upstream hydrocarbon revenue in Canada, and a 10-year CAGR of 9%. Conventional oil activity is predominantly attributed to the Prairie provinces as well as offshore activity on the East Coast, with Alberta estimated to account for 55%+ of historical conventional hydrocarbon revenue.

Based on actual and projected production results for 2024, Canada’s upstream hydrocarbon sector is expected to experience a -9% YoY reduction in total revenue, primarily due to commodity price declines. Nonetheless, there is optimism for aggregated revenues to improve going forward, largely due to additional takeaway capacity with TMX as well as additional processing capacity coming onstream in northeast BC in the Spring 2025. Additional pipeline egress, coupled with natural gas demand care of LNG demand off BC’s coast as well as in the Gulf of Mexico could equate to improved price differentials and a revenue rebound in the coming year.

Cut Through Noise with The Flyover!

One Email with ALL the News

Ditch the Mainstream Bias

Quick, informative news that cuts through noise.

OPERATING EXPENSES

Operating expenses tend to escalate alongside commodity prices. From 2017, costs experienced a 5.0% 8-year CAGR, which corresponds to the 6% 8-year CAGR of WTI crude oil price (annualized). This price-cost linkage is not necessarily unique to the oil and gas sector but is acutely pronounced in Canada due to bottlenecks in local labour availability and services relative to the resource base. That outsized labour demand is particularly apparent in the second chart above where average weekly earnings related to the Mining, Quarrying, Oil & Gas Extraction has steadily trended upwards from 2015, though at a 9-year CAGR of 2%. Nonetheless, operating costs have trended upwards, peaking during the 2021/22 inflationary spike following COVID where YoY cost inflation increased 19% and 30%, respectively. Inflationary pressures have dropped off in 2023 and 2024 as commodity steel and supply chain bottlenecks have normalized. Looking to 2025, expect to see further cost reductions on a per BOE basis due to further advancements in technology and operational efficiencies that correspond to the price outlook and the forecasted YoY price decline.

ROYALTIES

Canada's oil and gas royalty frameworks vary significantly across provinces, reflecting differences in geology, resource types, and fiscal policies. While each province has its own unique framework the underlying royalty due to the government follows an economic sliding scale based on commodity price and production. Royalties are tightly correlated to revenue, so when commodity prices are high and thereby generating a greater profit percentage so too will the royalty rate increase. Conversely, when commodity prices are low and production flattens, the byproduct is less revenue and a decreased royalty rate.

While the royalty rates for each province have been calculated, at a national level a simple rule of thumb is that for every $18B in annual revenue, the consolidated average royalty rate will increase +1% as a percentage of hydrocarbon-specific revenue. Example: for $200B in annual revenue the average royalty rate is 12% of revenue; for $218B in annual revenue the royalty rate as a percentage of revenue would increase +1%, equating to 13% of revenue. With FY24 revenues projected to finish down -10% YoY, I anticipate royalties to account for 10% of revenue, down from 12% of revenue in 2023.

Part 2 of the report will discuss trends related to cost of debt, operational cash flow and Capex, while finishing off with a summary of Canadian D&C activity and the financial analysis of Canada’s upstream sector.

COMPANIES MENTIONED

ATH: Athabasca Oil Corporation

CNQ: Canadian Natural Resources Limited

CVE: Cenovus Energy Inc.

CVX: Chevron Corporation

COP: ConocoPhillips Company

DVN: Devon Energy Corp

IMO: Imperial Oil Limited

IPC: International Petroleum Corporation

MEG: MEG Energy Corp.

MUR: Murphy Oil Corporation

NGTL: NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd.

SCR: Strathcona Resources Ltd.

SU: Suncor Energy

ACRONYMS

AECO: Alberta Energy Company. Refers to the benchmark spot price for Alberta natural gas on the Nova Gas Transmission Ltd. (NGTL) system. The term is used in reference to the spot price or assessed price for natural gas.

AER: Alberta Energy Regulator

BC: British Columbia

BOC: Bank of Canada

BOE/D: Barrels of oil equivalent per day

CAD: Canadian Dollar

CAGR: Compound Annual Growth Rate

D&C: Drilling and Completion

E&P: Exploration and Production

EBITDAX: Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, Amortization, and Exploration Expense

ESG: Environmental, Social, and Governance

FY: Fiscal Year

GJ: Gigajoule

LNG: Liquified Natural Gas

MMboepd: Million Barrels of Oil Equivalent Per Day

MMcfpd: Million Cubic Feet Per Day

NGL: Natural Gas Liquids

OPEC: Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries

SAGD: Steam-Assisted Gravity Drainage. Refers to a recovery technique for extraction of heavy oil or bitumen that involves drilling a pair of horizontal wells one above the other; one well is used for steam injection and the other for production.

SCO: Synthetic Crude Oil. Refers to the grade of oil that is similar to crude oil but is derived by upgrading bitumen from Oil Sands. The term is used in reference to the spot price of upgraded bitumen.

TMX: Trans Mountain Expansion

YoY: Year-over-Year

WCS: Western Canadian Select. Refers to the benchmark price for western Canadian crude blends. The price of other Canadian crude blends produced locally are also based on the price of the benchmark.

WTI: West Texas Intermediate. Refers to the grade of oil that serves as a benchmark oil price in the United States. The term is used in reference to the spot price or assessed price.

DISCLAIMER

All information contained in this publication has been researched and compiled from sources believed to be accurate and reliable at the time of publishing. However, in view of the natural scope for human and/or mechanical error, either at source or during production, Patrick Enwright accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss or damage resulting from errors, inaccuracies or omissions affecting any part of the publication. All information is provided without warranty, and Patrick Enwright makes no representation of warranty of any kind as to the accuracy or completeness of any information hereto contained.